Longitudinal Stability and Control: Flight dynamics form the cornerstone of aviation, with principles that dictate the behavior of aircraft during flight. Among the most critical components of flight dynamics is the longitudinal stability and control of an aircraft. This stability refers to an aircraft’s tendency to return to its original attitude after being disturbed along its longitudinal (nose-to-tail) axis.

In this article, we’ll delve into the intricacies of longitudinal stability, exploring its importance, the factors influencing it, and the control systems ensuring the safety and efficiency of flight.

Longitudinal Stability and Control

1. Basic Concepts

Before discussing longitudinal stability in-depth, it’s crucial to understand some foundational concepts.

- Axes of Rotation: Aircraft rotate around three primary axes:

- Longitudinal axis: Running from the nose to the tail of the aircraft. Rolling happens around this axis.

- Lateral axis: Running wingtip to wingtip. Pitching happens around this axis.

- Vertical axis: Running top to bottom of the aircraft. Yawing happens around this axis.

For our discussion, pitching motions around the lateral axis are of primary concern.

- Center of Gravity (CG): The point where the aircraft’s weight can be considered to be concentrated. It plays a pivotal role in longitudinal stability.

- Aerodynamic Center (AC): A point along the chord line of the wing where the pitching moment remains constant as the angle of attack changes.

- Neutral Point (NP): The point where the aircraft’s moment due to aerodynamic force changes equals zero.

2. Longitudinal Stability

Longitudinal stability is largely determined by the relative positions of the CG, AC, and NP.

- Positive Stability: When the aircraft returns to its original attitude after a disturbance. Typically, for positive stability, the CG should be ahead of the NP.

- Neutral Stability: The aircraft neither returns to its original attitude nor continues to pitch away. It remains in the new position after a disturbance.

- Negative Stability: The aircraft continues to pitch away from its original attitude after a disturbance. This is an undesirable characteristic in most conventional aircraft.

3. Factors Affecting Longitudinal Stability

- Wing Location: The position of the wing relative to the CG affects stability. High-wing aircraft tend to have a more stabilizing effect due to the pendulum effect, where the weight (CG) hangs below the lift.

- Stabilizer Size and Location: Horizontal stabilizers provide a counteracting moment to any pitching moment caused by the main wings. A larger stabilizer or one placed further back increases stability.

- Aircraft Loading: An improperly loaded aircraft, with a CG too far forward or aft, can drastically affect stability.

- Power Changes: In propeller-driven aircraft, changes in power can lead to changes in airflow over the wings and stabilizers, affecting pitch and stability.

- Aeroelastic Effects: These are changes in the aircraft’s structure during flight due to aerodynamic forces, which can influence stability.

4. Longitudinal Control

While stability is about the inherent behavior of an aircraft after a disturbance, control is about the pilot’s ability to command the aircraft’s attitude.

- Elevators: These are primary control surfaces located on the trailing edge of the horizontal stabilizer. They control the pitch of the aircraft.

- Trim Systems: These are secondary control systems that allow the pilot to adjust the neutral position of control surfaces, thus aiding in maintaining a desired attitude without continuous control input.

- Stick Force Gradient: This is a measure of how much force the pilot needs to apply to the control stick or yoke to change the aircraft’s pitch. A positive stick force gradient means that the pilot has to apply increasing force to achieve greater pitch angles, which is a desirable trait in aircraft design.

5. Dynamic Longitudinal Stability

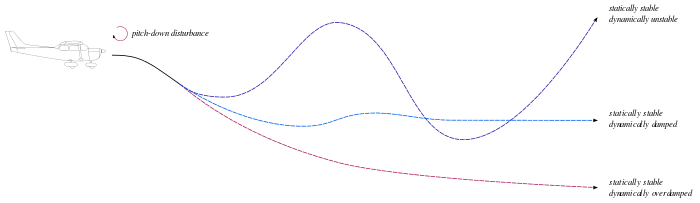

While static stability (as previously discussed) relates to the immediate reaction of an aircraft to a disturbance, dynamic stability pertains to the aircraft’s behavior over time following that disturbance.

- Phugoid Motion: A long-period oscillation involving changes in altitude and airspeed but little change in pitch angle. It’s a slow, seesawing motion between kinetic and potential energy.

- Short Period Oscillation: A rapid oscillation in pitch, usually with a constant altitude. This motion is typically of more concern than phugoid as it can be uncomfortable or even dangerous if amplitudes are large.

6. Modern Enhancements to Longitudinal Stability and Control

With the advancements in aviation technology, several systems have been developed to enhance longitudinal stability and control.

- Fly-by-wire Systems: Electronic systems that replace traditional manual controls. They can automatically adjust control surfaces to maintain stability, often faster than a pilot can.

- Stability Augmentation Systems (SAS): These are automatic systems that make corrections to control surfaces to enhance the inherent stability characteristics of the aircraft.

- Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD): This advanced analytical tool allows engineers to predict airflow and stability characteristics with computer simulations, leading to better aircraft designs.

Longitudinal stability and control are paramount to the safe and efficient operation of an aircraft. Through understanding the principles and factors influencing this aspect of flight dynamics, engineers can design aircraft that not only perform well but also ensure the safety of their occupants.

In the ever-evolving field of aviation, continuous research and advancements are being made to enhance the longitudinal stability and control of aircraft, merging the boundaries of human capability with technological innovation. The flight dynamics principles discussed herein will continue to be foundational in guiding the future of aircraft design and operation.